Tax Multiplier Definition in Economics

The tax multiplier in economics is defined as the factor by which a change in taxes will alter GDP. With this tool, the government is able to decrease (increase) taxes by the exact amount that they need GDP to rise (decline). This allows the government to make a precise tax change rather than an estimation.

Whether it's every week, two weeks, or a month, you have two decisions to make when you deposit your paycheck: spend or save. Saving and spending your money will have a big influence on GDP due to the tax multiplier effect.

A 10% decrease in taxes will not yield a 10% increase in aggregate demand. The reason for that is outlined in our paycheck example above — when you receive some transfer, you will choose to save and spend some portion of it. The portion you spend will contribute to aggregate demand; the portion you save will not contribute to aggregate demand.

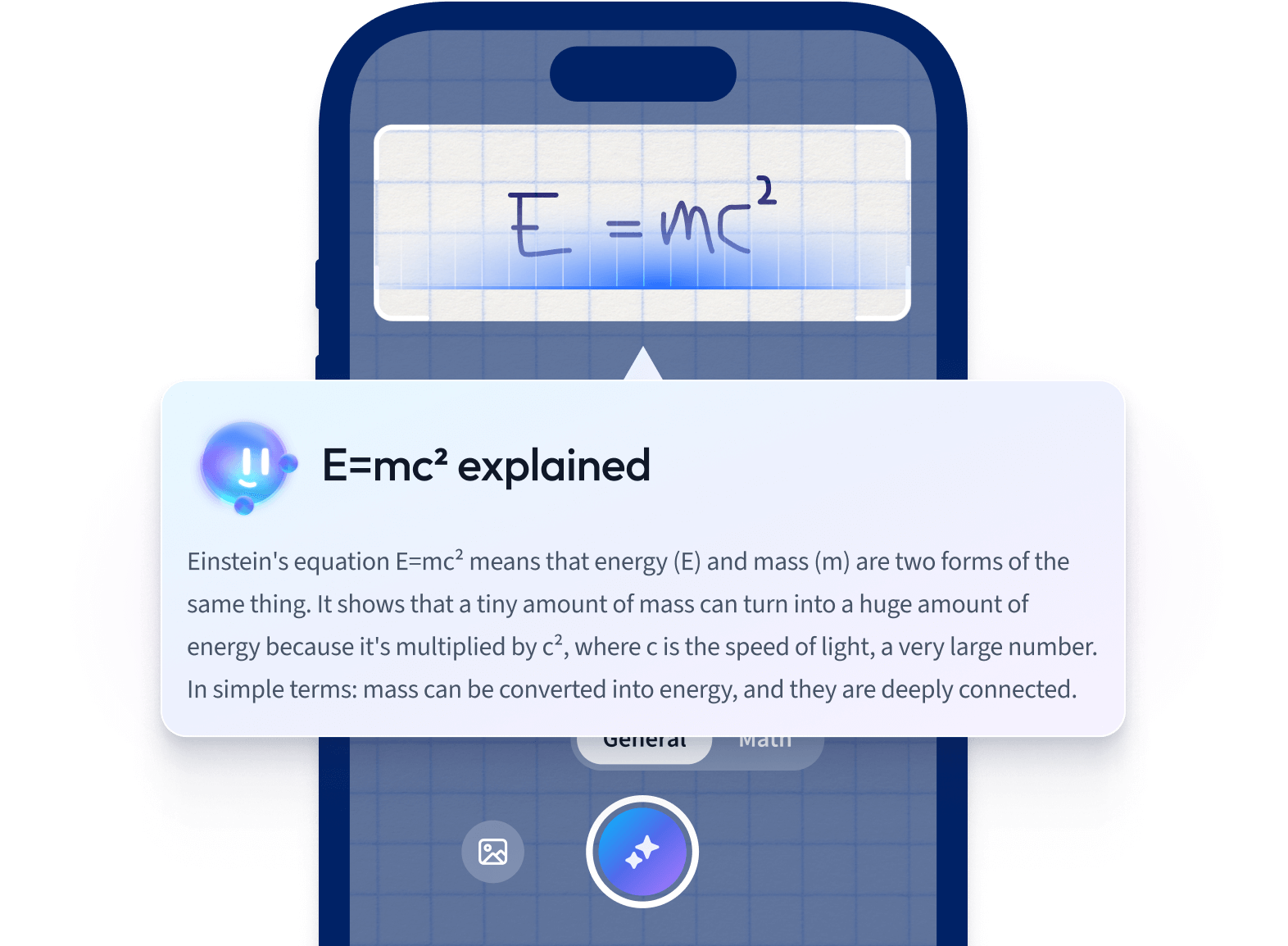

But how can we determine the change in GDP after altering taxes like the ones in figure 1?

The answer is - through the tax multiplier!

Fig 1. - Calculating Taxes

Fig 1. - Calculating Taxes

The simple tax multiplier is another way people often refer to the tax multiplier.

You may see it referred to like both — do not get confused!

Tax Multiplier Effect

Depending on whether fiscal policy actions increase or decrease taxes will change the tax multiplier effect. Taxes and consumer spending are inversely related: increasing taxes will decrease consumer spending. Therefore, governments need to know what the current state of the economy is before altering any taxes. A recessionary period will call for lowers taxes, whereas an inflationary period will call for higher taxes.

The multiplier effect occurs when money can be spent by consumers. If more money is available to consumers, then more spending will occur — this will lead to an increase in aggregate demand. If less money is available to consumers, then less spending will occur — this will lead to a decrease in aggregate demand. Governments can utilize the multiplier effect with the tax multiplier equation to alter aggregate demand.

Fig 2. - Increasing aggregate demand

Fig 2. - Increasing aggregate demand

The graph above in figure 2 shows an economy in a recessionary period at P1 and Y1. A tax decrease will allow customers to spend more of their money since less of it is going to taxes. This will increase aggregate demand and allow the economy to reach equilibrium at P2 and Y2.

Tax Multiplier Equation

The tax multiplier equation is the following:

The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the amount a household will spend from each additional $1 added to their income. The marginal propensity to save (MPS) is the amount a household will save from each additional $1 added to their income. The formula also has a negative sign in front of the fraction since a decrease in taxes will increase spending.

The MPC and MPS will always equal 1 when added together. Per $1, any amount that you do not save will be spent, and vice versa. Therefore, MPC and MPS must equal 1 when added together since you can only spend or save part of the $1.

Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) is the amount a household will spend from each additional $1 added to their income.

Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS) is the amount a household will save from each additional $1 added to their income.

Tax and Spending Multiplier Relationship

The tax multiplier will increase aggregate demand by a smaller amount than the spending multiplier. This is because when a government spends money, it will spend the exact amount of money that the government agreed to — say $100 billion. In contrast, a tax cut will incentivize people to spend only a portion of the tax cut while they save the rest. This will always lead to the tax cut being "weaker" in comparison to the spending multiplier.

Tax Multiplier Example

Let's look at a tax multiplier example. Governments use the tax multiplier to determine what the change in taxes should be. Simply knowing whether to increase or decrease taxes is not sufficient. We will go over two examples.

Tax Multiplier Example: Multiplier Effects on Spending

We will have to make a few assumptions to complete an example. We will assume that the government plans to increase taxes by $50 billion, and the MPC and MPS is .8 and .2 respectively. Remember, they both have to add up to 1!

What does the answer tell us? When the government raises taxes by $50 billion, then the spending will go down by $200 billion given our tax multiplier. This brief example provides the government with very important information.

This example shows that governments need to carefully alter taxes to get an economy out of an inflationary or recessionary period!

Tax Multiplier Example: Calculating for a specific Tax Change

We went over a brief example of how spending is affected by a change in taxes. Now, we will look at a more practical example of how governments may use the tax multiplier to address a specific economic issue.

We will have to make a few assumptions to complete this example. We will assume that the economy is in a recession and needs to increase spending by $40 billion. The MPC and MPS is .8 and .2 respectively.

How should the government change its taxes to address the recession?

What does this mean? If the government wants to increase spending by $40 billion, then the government needs to decrease taxes by $10 billion. Intuitively, this makes sense — a decrease in taxes should stimulate the economy and incentivize people to spend more.

Tax multiplier - Key takeaways

- The tax multiplier is the factor by which a change in taxes will alter GDP.

- The multiplier effect occurs when consumers can spend part of their money in the economy.

- Taxes and consumer spending are inversely related — an increase in taxes will decrease consumer spending.

- Tax multiplier = –MPC/MPS

- Marginal Propensity to Consume and Marginal Propensity to Save will always add up to 1.

How we ensure our content is accurate and trustworthy?

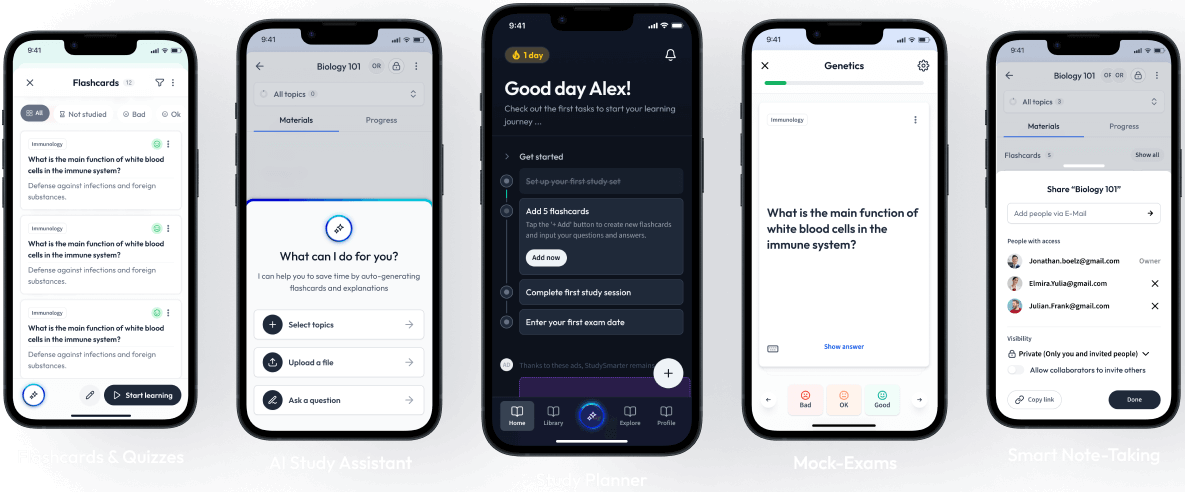

At StudySmarter, we have created a learning platform that serves millions of students. Meet

the people who work hard to deliver fact based content as well as making sure it is verified.

Content Creation Process:

Lily Hulatt is a Digital Content Specialist with over three years of experience in content strategy and curriculum design. She gained her PhD in English Literature from Durham University in 2022, taught in Durham University’s English Studies Department, and has contributed to a number of publications. Lily specialises in English Literature, English Language, History, and Philosophy.

Get to know Lily

Content Quality Monitored by:

Gabriel Freitas is an AI Engineer with a solid experience in software development, machine learning algorithms, and generative AI, including large language models’ (LLMs) applications. Graduated in Electrical Engineering at the University of São Paulo, he is currently pursuing an MSc in Computer Engineering at the University of Campinas, specializing in machine learning topics. Gabriel has a strong background in software engineering and has worked on projects involving computer vision, embedded AI, and LLM applications.

Get to know Gabriel